My grandfather Norman Vanek was of 100 percent Czech descent. All of his great-grandparents and some of his great-great grandparents were Czech immigrants. They came to America at different times between 1855 and 1883, the early arrivals settling first along the shore of Lake Michigan between Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, and Chicago, Illinois. In 1869 and 1870, those in Wisconsin and Illinois migrated to Saline County, in southeastern Nebraska, on land that was then just beyond the western terminus of the local railroad line. Later immigrants from Bohemia joined those already in Saline County, creating one of the most densely populated Czech settlements in America.

For all of these former Czech peasants, the fertile farmland of Saline County represented an opportunity to improve their lives. Most of them got by on 80 or 160 acres—small to average-sized farms in late 19th century Nebraska. While this was significantly better than the tiny plots they had owned or rented in Bohemia, most of Norm’s ancestors were far from the wealthiest people even in their own township. They struggled the iconic struggles of pioneers on the prairie: dugouts and sod houses, grasshopper plagues, heat waves and blizzards, and the perpetual risks of epidemic disease and farm accidents.

Jacob Kobes and his wife Marie Filipi stood apart from the rest of Norman’s ancestors. They overcame these challenges and prospered. Of course, even in America, the land of promise, success took good sense, a lot of hard work, and a little bit of luck. Jacob had all three, at least until his luck ran out one tragic day in 1895. Jacob’s is the next story in the series “You Died How?,” which looks at all the strange ways my ancestors died.

A Lucky Start

Let’s start with luck. Jacob was lucky to have survived infancy. His parents, Johann Kobes and Katerina Kwitek, came from peasant families in western Bohemia, not far from the German border. Johann had been born in the village of Havlovice and Katerina in the small town of Mrákov.

When their marriage was recorded August 9, 1826, in the Roman Catholic Church in Mrákov, Johann was listed as a chalupner, a German spelling of the Czech word chalupnik, meaning peasant cottager. Johann may have owned a garden plot or a few acres of his own, as well as a small cottage, but he also had to work as a day laborer, farmhand, or petty craftsman to make ends meet. He was still listed as a chalupner when his son Jacob was born on July 24, 1849, almost 23 years after the wedding. In short, while Johann and Katerina were not the poorest of the poor, they had little hope of upward mobility.

Johann and Katerina Kobes suffered more than their share of loss. According to parish records, the couple lost four of their eight children as infants or toddlers. Jacob was their only son to survive to adulthood. In fact, he was the third child to whom his parents had given the name Jacob. The other two Jacobs, born in 1829 and 1833, each died before reaching age two. Another older brother, Andreas, born in 1836, only reached two-and-a-half before he died. Our Jacob was the only boy in his family to reach age three, much less middle age. He survived the widespread childhood diseases that ravaged peasant families across Europe and probably killed four of his siblings. (Three of Jacob’s four sisters lived long lives; the fourth, Dorothea, born in 1842, died after only three short months of life.) Such a high rate of infant mortality was sadly typical in 19th century Europe, especially in families of peasants and the urban working class.

Jacob was also lucky to survive considering his mother’s age. It may have been something of a surprise when Katerina found out she was pregnant in late 1848. She was 40 years old and—at least as far as parish records tell us of her pregnancies—had not given birth in more than seven years.

On the Move

Jacob grew up in the village of Havlovice. He was almost an only child, since his three surviving sisters were so much older than him. As a little boy, he probably played with nieces and nephews as much as cousins. His older sisters Maria (b: 1827) and Anna (b: 1831) had married and begun having children Havlovice before Jacob was even born. Before he was too old, however, his family made the life-changing decision to leave their homeland for new and better opportunities in America.

In the mid 1850s, Maria (now Schleiss) and Anna (now Kovarik) and their families were the first to emigrate. They joined dozens of other Czech emigrant families that chose to settle in Manitowoc County, Wisconsin. Johann and Katerina soon brought Jacob and his sister Katherine (b: 1839) to join them. In 1860, we find Johann and Katerina on a farm in Kossuth Township, with just Jacob still at home. His sister Katherine had married Bohemian immigrant Jacob Hulec (pronounced Huletz) the preceding November.

At some point in the mid 1860s, the Kobes family followed the Lake Michigan shoreline south to Racine County, Wisconsin, south of Milwaukee. I haven’t found any primary-source records of them there, but the obituary of Jacob’s sister Katherine says she lived there for a time, and there is also evidence Jacob’s future wife Marie Filipi was there. Jacob married Marie, probably in Racine County, in about 1868. She was just 13 or 14 years old.

In 1867, Jacob’s sister Anna and brother-in-law Joseph Kovarik packed up and moved their family to Saline County, Nebraska. They were the family’s explorers, checking out the frontier of white settlement and giving prairie life a try. Joseph Kovarik claimed 80 acres under the 1862 Homestead Act and built a sod-roofed dugout for his family to live in.

In fact, Homestead claims tell us that everyone in the Kobes and Filipi families initially lived in dugouts like this one for a couple years before they were able to buy enough lumber to build log cabins. The Filipis lived in their dugout for exactly two years. The Kovariks lived in theirs for at least five years and perhaps longer.

Rosicky, Rose. A History of Czechs (Bohemians) in Nebraska. Omaha: Czech Historical Society of Nebraska and the National Printing Company, 1929, pp 70-97. Published online here.

In 1869, the rest of the Kobes family followed Anna to Nebraska, with one exception. Jacob’s father Johann died around this time, probably in Wisconsin. There is a small chance he made it to Nebraska—a list of early Czech settlers published in the 1920s includes “John Kobes, Havlovice” as a pre-1870 settler and no other John Kobeses lived in the county as far as I can tell. However, Katerina called herself a widow on the Homestead claim she made in 1869 and John is absent from the 1870 census.

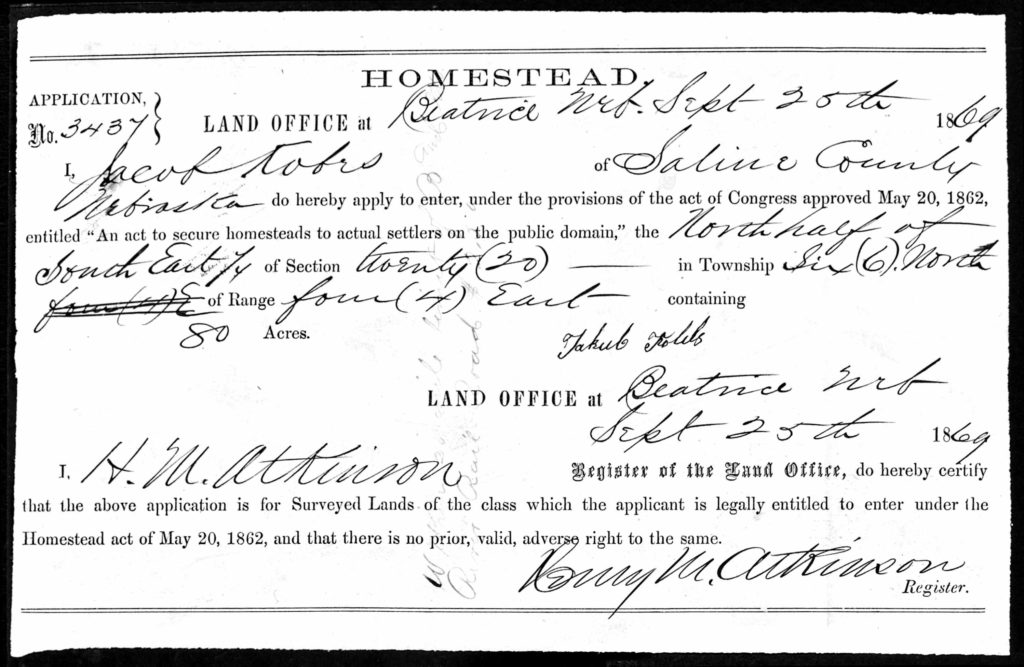

Without Johann, the 1869 migrant group included Jacob and his new wife Marie, Jacob’s mother Katerina, his other married sisters, and his new in-laws Frantisek and Josefina Filipi and the rest of their children. That summer, Jacob and Marie settled on 80 acres of land three miles southwest of the village of Wilber. Just like the Kovariks, they first constructed an iconic pioneer dugout. Jacob filed a Homestead claim for the land on September 25. Both Jacob’s mother Katerina (acting as an independent widow) and his father-in-law Frantisek Filipi claimed 80 adjacent acres the same September day. His brothers-in-law Fredrich Schleiss and Jacob Hulec and nephew Wenzel Schleiss each also made a nearby claim within the next six months. Collectively, Jacob’s extended family claimed 480 acres of excellent farmland and they paid a total of just $84 in filing fees to get it. Even though they all lived in sod-covered dugouts and would not hold the title to any of this land for another five years, the future looked far brighter than it ever would have in Bohemia.

Prospering

Jacob was twenty when he put in his Homestead claim. He was old enough to fend for himself. He had learned enough skills not just to survive but to thrive, including many that had probably been imparted by his late father. We know, for example, that Jacob had a knack for managing money. When men in the community gathered to create the new Czechoslovak cemetery in 1874, Jacob Kobes was chosen as one of two trustees. (Joseph Kobes, who sold the land for the cemetery and became president of the cemetery organization, was Jacob’s double 1st cousin. Their fathers were brothers and their mothers were sisters.)

Jacob was obviously ambitious and hard working. Consider what he accomplished in his first first five years on the land. According to his Homestead paperwork, he built two houses, first a 14 x 16 foot dugout and then a “good, comfortable” 16 x 18 foot log house, brought 55 acres of prairie land under cultivation, constructed “a stable, granary, and corn cribs, bored and tubed a well, and set out 2 acres of forest trees.” In spite of grasshopper plagues in 1874 and 1876 that destroyed the region’s entire corn crop and a serious flood of Turkey Creek in 1875 that may have inundated the Kobes land, the family prospered and Jacob was able to buy more land.

By 1880, Jacob had purchased an additional 160 acres of adjacent land for a total of 240 acres. (80 of those acres were the ones his mother had Homesteaded in 1869.) He had 120 acres under till and grew a surprisingly diverse range of crops (in order of acreage): wheat, corn, oats, barley, rye, and potatoes. He owned more poultry than any of my other Czech ancestors and had a decent number of cattle, pigs, and horses. To help him manage so many different things, Jacob had employed a total of 56 weeks worth of hired labor in 1879. The total value of his farm was more in line with the established farms owned by my old-stock American ancestors in Illinois than with any of my other Czech pioneer ancestors in Nebraska.

For Jacob, more land meant more profits with which to buy more land. By the early 1890s, he owned 400 acres (see pg. 31 of hyperlink). I believe he had inherited or purchased 160 acres after the death of his father-in-law Frantisek Filipi in a freak winter accident in 1886. At the time of Jacob’s own death in 1895, his estate totaled 480 acres.

Throughout these years, his family was growing. Marie gave birth to her first child, my great-great-grandfather Joseph, in November 1870, probably in the dugout they had built the year before. Daughter Anna followed in 1872. Unfortunately, Jacob and Marie then had to deal with the same sad loss Jacob’s parents had faced. In 1874 they buried their daughter Ema, who had lived only eight months. She was one of the first people buried in the new cemetery. Then son Adolf, born in 1876, died in early January 1878 aged 17 months. Thankfully, three more healthy children arrived after that: Adolph (1878), Albena (1880), and Emma (1882). Just like Jacob’s parents had done, he and Marie chose to name later children in honor of deceased older siblings.

“Another Serious Accident”

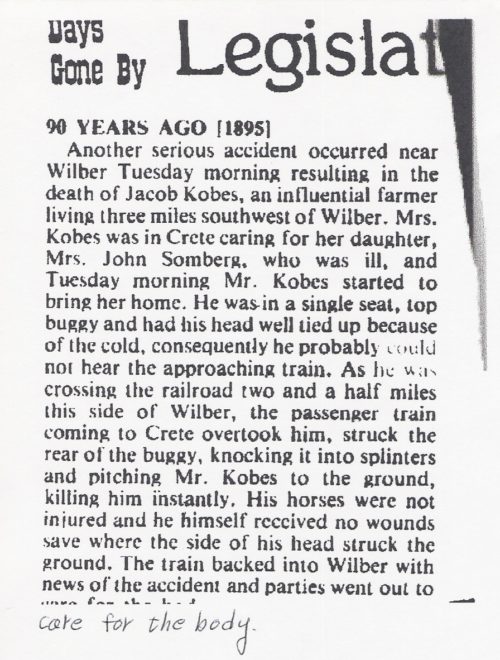

All thing considered, Jacob had been incredibly lucky. He survived infancy when half of his siblings did not. He survived a transatlantic voyage and repeated moves within the United States. He survived inhospitable prairie weather and the social stigma of living in a dugout. He overcame grasshopper plagues and floods and carried on despite losing two of his children. By the mid 1890s, he was a well known and “influential farmer” in Wilber. From the perspective of a Bohemian peasant boy, his landholdings and the financial security they represented would have been beyond belief. But his luck ran out in the winter of 1895.

It was the middle of February. It was cold. Nine days that month the temperature dropped below zero in nearby Lincoln. Jacob’s wife Marie was staying at the home of their daughter Anna—now the wife of John Somberg—in Crete, a town eleven miles north of Wilber. Anna had been sick and Marie had gone to care for her. On Tuesday, February 19, Jacob hitched two horses up to his “single seat, top buggy” and started out for Crete to fetch Marie. He made his way into Wilber and then turned north on the main road to Crete. About two-and-a-half miles north of Wilber, the road crossed the tracks of the Lincoln–Wymore line of the Burlington and Missouri Railroad. (You can trace Jacob’s course on this roughly contemporaneous plat map. Look for his property in section 20 and the railroad crossing in section 3.)

As one local newspaper reported, Jacob “had his head tied up well because of the cold, consequently he probably could not hear the approaching train. As he was crossing the tracks . . . the passenger train coming to Crete overtook him, struck the rear of the buggy, knocking it into splinters and pitching Mr. Kobes to the ground, killing him instantly. His horses were not injured and he himself received no wounds save where the side of his head struck the ground.”

The sudden and tragic death of Jacob Kobes at the age of 45 was undoubtedly hard on his family. And yet, compared to the consequences of some of the other unfortunate deaths we’ve examined in this series—take Dolphis Dupre, for example—Jacob’s family was going to be OK. His youngest child was 11. Even if the worst imaginable circumstances arose, he left enough property that its sale could keep the family secure for a while.

Jacob’s estate was apparently not legally dispersed until after 1900. Until then, it was de facto in possession of the widow Marie. Eventually, eldest son Joseph took ownership of the eastern 280 acres, including the land originally homesteaded by his grandmother Katerina Kwitek Kobes and grandfather Frank Filipi and half the land homesteaded by his father Jacob. Younger son Adolph got the western 200 acres, including the other half of Jacob’s original claim.

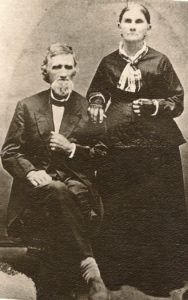

This small portrait at right was displayed at Jacob’s funeral (below). It is the only photograph of Jacob I’ve ever come across. Some distant cousin may still have the original among their family photographs, but it might be gone forever. That would be another unfortunate and unnecessary loss.

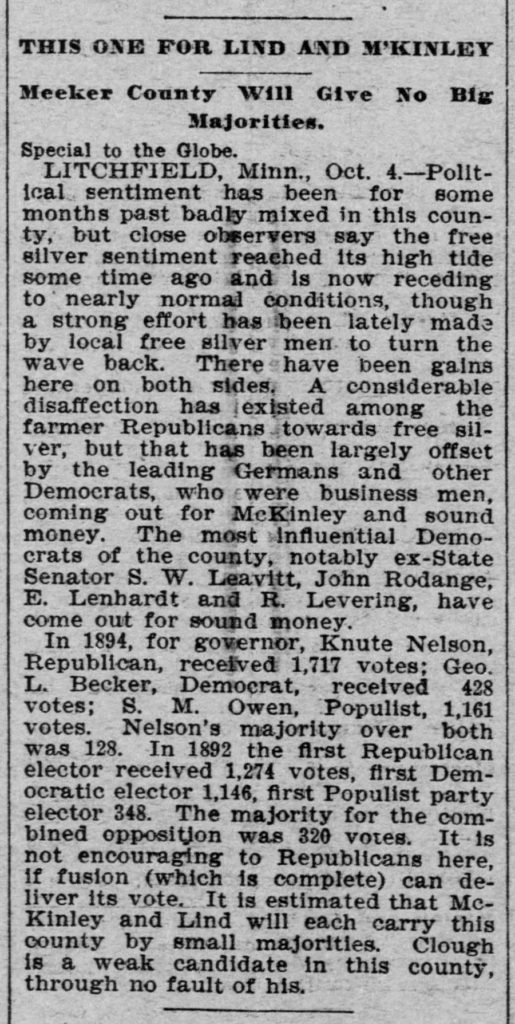

Trains have always been dangerous. It’s difficult for them to stop and they can’t deviate from the course of the tracks. Jacob’s story reminds us that railroad workers were not the only ones who suffered injuries and deaths around railroads. Surprisingly, Jacob isn’t the only relative of mine to die being hit by a train. My 5x-great-grandfather James Daly lost a brother-in-law in very similar fashion. The administrator of Morgan Hussey’s Findagrave page quotes a story published in the McKean County Miner [Penn.], November 2, 1883:

“Mr. Morgan Hussey, of Keating township, met with a sudden death while walking on the track of the Philadelphia & Erie railroad, near Sterling Run, on Wednesday. He was visiting his daughter at that place, and for some purpose started out to walk down the track. He was a very old man, and quite deaf, and not hearing the express train which came upon him was killed instantly. Mr. Hussey had been a resident of this county nearly half a century and by hard work and economy had assumed a comfortable property. His funeral will take place here today from St. Elizabeth’s church.”

My takeaway is, never go near railroad tracks when you’re visiting your daughter!

Do any of you have crazy stories of railroad accidents from your families?

The Family Tree Guide to DNA Testing and Genetic Genealogy is as good a book as one could imagine for this market. Sure, some of its content will be out-of-date by next year, but it succeeds in every aspect Bettinger and the publisher could control. Everyone from beginners to professional genealogists will find value in it.

The Family Tree Guide to DNA Testing and Genetic Genealogy is as good a book as one could imagine for this market. Sure, some of its content will be out-of-date by next year, but it succeeds in every aspect Bettinger and the publisher could control. Everyone from beginners to professional genealogists will find value in it.

![Burgess Nelson deed to free his two slaves. Report of Manumissions, Frederick County, March 10, 1836, Henry Schley: Burgess Nelson will free Negro Elizabeth Ann in 1840 and John in 1852 [Frederick County]. Maryland Manuscripts collection, item 3124. http://digital.lib.umd.edu/image?pid=umd:89361](http://www.genealogicresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Burgess-Nelson-Report-of-Manumission-1836-Frederick-County-MD2-page-001-839x1024.jpg)