I recently led my mom and the rest of my immediate family on a fun day exploring family history in our own backyard. We toured of part of the region to which my mom never thought she had any special connection: the city of Minneapolis.

My mom always knew she had deep roots in Minnesota, especially to the city of St. Paul and its suburbs. She grew up in St. Paul. Her mother grew up there. Her maternal grandfather worked for years in the stockyards in South St. Paul. My mom also knew that some her father’s French-Canadian ancestors had lived in St. Paul’s northern suburbs of Little Canada and Centerville for generations, and she had an inkling a few of them had once been in St. Paul, too. (Indeed, one family was among the very first to stake claims in the future state capital in 1837, and in 1841 they donated half the land for the Catholic church that gave the city its name.)

When I first asked my mom and her brothers if we had any direct ties to Minneapolis—the western “twin” of the Twin Cities—they didn’t know. They didn’t think so. I was disappointed by that answer. I grew up in the western suburbs of the Twin Cities. When we went into “the city” for a concert or a baseball game or the farmer’s market, it was almost always to Minneapolis not St. Paul. My dad worked in one of the skyscrapers in downtown Minneapolis. When people from outside Minnesota asked me where I was from, I usually said Minneapolis. As I researched my mom’s family, I wanted to have some relationship to the city’s history. That’s where the action was when I was growing up. That’s where most of the action has been for a century and a half.

Since the 1850s, Minneapolis has been the beating heart of the regional economy. While St. Paul grew into a major city because it was the head of navigation on the Mississippi River and the state capital, Minneapolis grew even bigger because it had the Mississippi River’s only natural waterfall. St. Anthony Falls powered the city’s industries, transforming it into a global saw- and flour-milling superpower by 1880. Its mills processed grain from southern and western Minnesota and the Dakotas and timber from the vast north woods. (Recognizable brand names from this era of Minneapolis history include Pillsbury and Gold Medal Flour.) If my family’s collective memory was all we had to go on, then our family story remained peripheral to the story of Minneapolis. They lived in St. Paul and in the metropolitan area’s agricultural hinterland, but not in industrial Minneapolis.

However, as I researched our LaBelle ancestors (the surname my mom and uncles were born with), I discovered that, in fact, three generations had lived, worked, fell in love, and died in the heart of the Minneapolis Mill District over the course of more than thirty years.

What follows is, first, a narrative of my family’s ties to the St. Anthony Mill District of old Minneapolis, and second, a rundown of the LaBelle family history tour on which I recently led my family.

Coming to Minneapolis

The story of the LaBelle migration to Minneapolis is long and complicated. I won’t detail it all here. It was a case of serial migration that lasted at least thirty years, from 1848 to 1878, and included three generations of migrants. The patriarchs were two brothers, Pierre (b: 1799) and Alarie Lebel (b: 1801). (The name had been spelled Lebel in Canada ever since Nicolas Lebel arrived in New France in 1654. LaBelle became the standard form in the U.S.) The migration started from a single spot—their family farms near Gentilly, Quebec—but it ended in towns across the northern United States. Descendants of Pierre and Alarie helped construct the final stretches of the transcontinental railroad in Wyoming, logged and sawed timber in northern Wisconsin, ran a saloon and grocery store in Bay City, Michigan, and became laborers and carpenters in Minneapolis. One descendent named George LaBelle ran the largest automobile-based transportation company in the Twin Cities in the mid 1920s and in 1928 was a founding partner in the Allied Van Lines cooperative.

My direct ancestral line brought up the rear. Patriarch Alarie Lebel was already an old man—a 65-year-old widower—when he first came to the United States in 1866. It appears he was cared for in turn by his various children. He settled first with the family of his son Uldorique (Roderick) in Brown County, Wisconsin. That’s where some of Alarie’s nieces and nephews (Pierre’s children) had settled in the late 1840s. By 1880, ol’ man “Alarie” had moved to Bay City, Michigan, where his daughter Adeline and her husband Patrick Pelletier ran a grocery store. Only in 1881, when Alarie was 80 years old, does he show up in the Minneapolis city directory for the first time. By 1881, Minneapolis made the most sense for Alarie to be cared for by his children. In the preceding decade, his children Ovid, Noah, Philonese, Olive, and Roderick had all moved to the city.

Alarie’s eldest son Ovid Lebel (b: 1831) is my direct ancestor. It appears he was the last member of the family to leave Quebec. My hunch is that Ovid was in line to inherit the family farm in Gentilly. Word from relatives must have convinced him and his wife Rosalie Goudreau that they could do better in America. Or perhaps Ovid believed he needed help caring for Rosalie, who began showing symptoms of some sort of mental illness in the early 1870s. (More on this below). Ovid and family came to the United States between 1875 and 1877, settling first in Houghton County, Michigan, in the Upper Peninsula, and then trickling into Minneapolis during the summer and fall of 1878. Among the children Ovid and Rosalie brought with them was their sixteen-year-old son Ferdinand (b: 1862), my great-great-grandfather.

A Hard Life Along the Riverfront

The LaBelles needed work and Minneapolis needed workers. Upon arriving in the city, Ovid’s family moved straight into the heart of the mill district on the east bank of the Mississippi River. Ovid and the couple’s older sons found plenty of work as day laborers. The family couldn’t afford much for living quarters. In fact, the LaBelles’ first residence in Minneapolis was the oldest house in the city. Ovid’s 1913 obituary states quite clearly (in French) that “35 years ago he resided in the Godfrey House, the first house constructed in Minneapolis.”

Nowadays, the Ard Godfrey House is preserved as a museum, a memorial to the earliest Euro-American settlement at St. Anthony Falls. In 1848, prominent early Minnesota businessman Franklin Steele hired Maine native Ard Godfrey to build the first dam and commercial sawmill at the falls. As part of the deal to bring Godfrey west, Steele agreed to build a house for Godfrey and his family. According to a 1983 report on the house’s history, two French-Canadians, Charles Mousseau and James Brissette, built the small but surprisingly spacious five-bedroom home for Godfrey’s family to live in. The house stood on the east side of the river in an area that would be incorporated as the city of St. Anthony in 1855. The Godfrey family vacated the house in 1853 in order to move across the river to Minneapolis. There Ard Godfrey built a new home and mill just below Minnehaha Falls. (St. Anthony and Minneapolis merged in 1872.)

When the LaBelles arrived in the late 1870s, the Godfrey house remained in practically its original location near the riverfront. By then the dense St. Anthony mill district had been built around it. Nobody yet cared that the house was historic. It was simply old and probably a little rundown. It certainly was not in a desirable location. The area was noisy and dirty. On the same block could be found two iron foundries, a machine shop, and a warehouse, according to an 1885 Sanborn insurance map. Yet the fact that the home had five bedrooms and was close to so many industrial jobs made it a suitable boarding house. Newly arrived immigrants piled in family upon family.

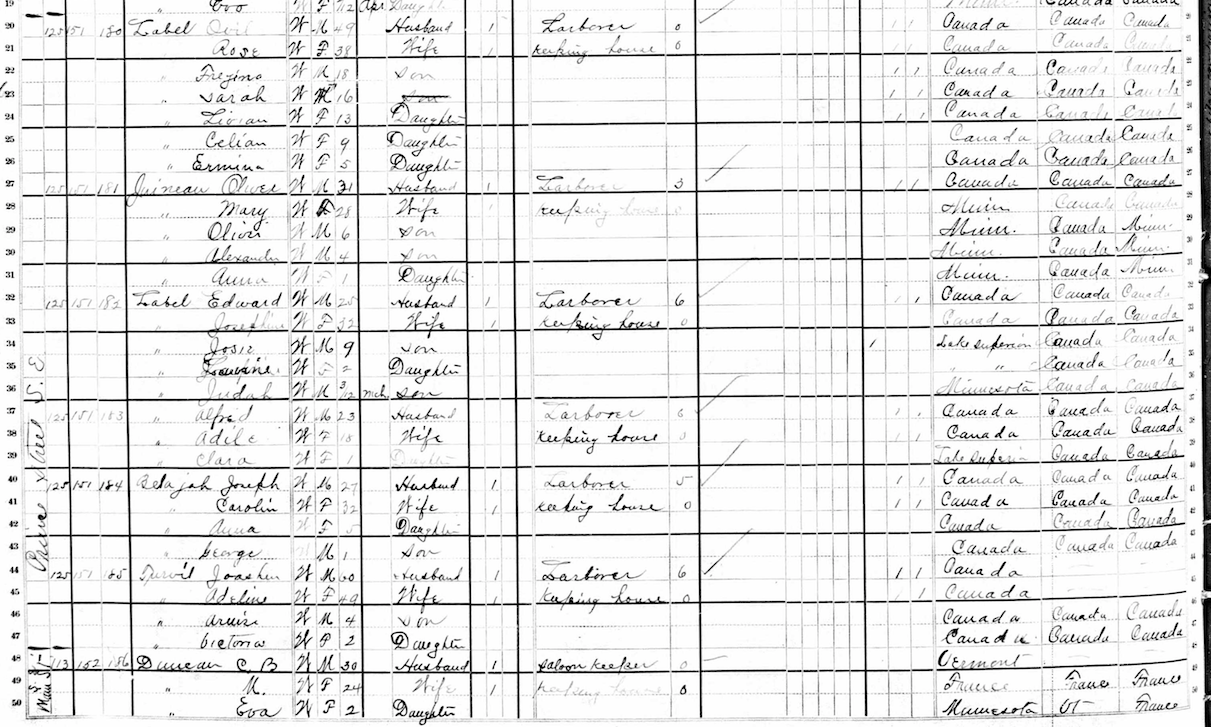

When the 1880 census was taken, 28 people from six families were enumerated at the one and only address on the 100 block of Prince Street (site of the Godfrey House):

- Ovid and Rose “Label” and five children

- Oliver and Mary Juneau with three children

- Ovid and Rose’s son Edward Label with his wife Josephine and three children

- Ovid and Rose’s son Alfred Label with his wife Adele and one child

- Joseph and Caroline “Belajah” [Belanger?] with two children

- “Joashem” [Joachim] and Adeline “Turvil” with two children. Joachim Duteau dit Tourville was Ovid LaBelle’s maternal uncle, the younger brother of his deceased mother Genevieve.

All of the adults in the house had been born in French Canada. The adult males were all recorded as laborers. Since city directory listings for 1879 and 1880 suggest Ovid and Edward LaBelle had not moved from their original address in the city and since we know the Godfrey House was on the 100 block of Prince Street, we can safely conclude that these 28 people were all living in the Godfrey House in 1880. Each family probably rented a single room in the house while sharing use of the kitchen wing.

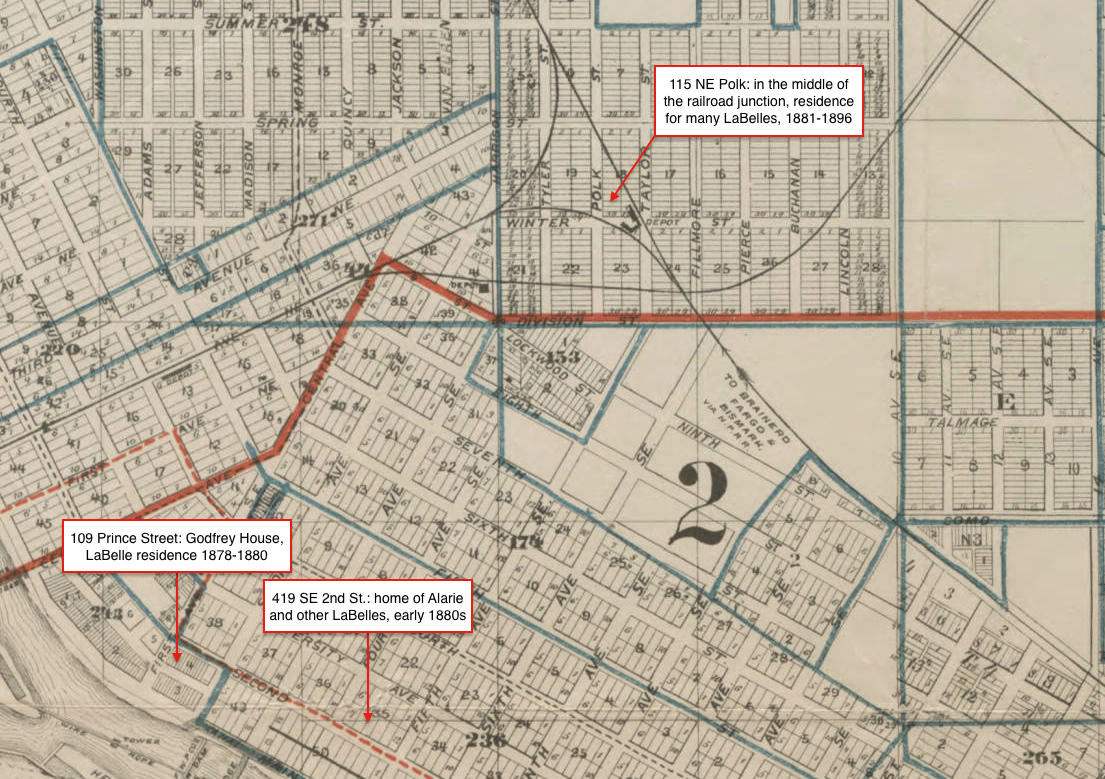

Another resident of the Godfrey House around this time was Zephirin Poisson (b: 1853), a French-Canadian man who also hailed from Gentilly. In America, he usually went by the name Frank Fish. His address in the 1879 Minneapolis city directory—Prince St. near 2nd Ave. SE—is identical to the address given for Ovid, Edward and Noah LaBelle. Zephirin’s first wife, Delia Tourville (b: abt 1849), was a daughter of Joachim and Adeline. Delia died in 1882, and in 1883 Zephirin married his second wife, Ovid and Rosalie LaBelle’s daughter Olivine (b: 1867). The LaBelles, Tourvilles, and Poissons obviously knew one another going back to Gentilly, but I suspect Zephirin and Olivine first noticed one another while they both lived at the Godfrey House in 1879. In any case, when Zephirin and Delia moved out of the Godfrey House later that year, they moved just a couple blocks east, to 419 Southeast 2nd Street, where they resided with several other members of the LaBelle family: Louis, Noah, and their families, as well as patriarch Alarie when he arrived in Minneapolis in late 1880 or early 1881.

The LaBelles were obviously poor. Ovid’s next residence near the corner of Polk and Winter Streets, where he lived continuously (with one exception) from 1881 to 1896, was first recorded without a street address simply as “near the junction of the St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba Railroad.” Old city maps show that the house was literally in the middle of a railroad junction. Several other listings mention that Ovid lived “in the rear of building” at that address, which likewise suggests poverty. The railroad junction still exists, but the street grid has long since been removed for safety. Polk St. and Winter St. no longer intersect.

Sudden Passions

Ovid’s wife Rosalie Goudreau LaBelle also moved to the house by the railroad junction in late 1880 or early 1881. However, her stay was much shorter. Rosalie suffered from some kind of mental illness. She was diagnosed with dementia, though I suspect modern doctors would call it something else. Since the early 1870s, she had been a difficult person to live with. She sometimes broke out in “sudden passion[s]” and “threaten[ed] others with injury.” Barely a year after they settled in Minneapolis, in December 1879, the family sought to have Rosalie committed to the state and placed in an insane asylum. She was committed by the probate judge but remained at home with her family until 1883. On June 29, 1883, she was sent to the Minnesota Asylum for the Insane in St. Peter.

Doctor’s notes tell us that she did ok there in the following years. A note from August 1884 says she was “very pleasant and quiet . . . contented and apparently happy.” A year later she was described as “slightly more irritable” but by 1886 and ’87 she was “fat and hearty” and “fat and happy.” From a modern perspective of mental health, perhaps the most telling indication of her well-being at the asylum was the statement made in 1884 that she “is very quiet but this may in part be due to the fact that no one in the hall can talk French to her.” Social isolation could not have helped her state of mind.

After four years, three months and two days in the asylum, Rosalie was released from the hospital and returned to Minneapolis to live with her family. Her condition had “improved” but she was not fully “recovered.” The final notes, from October 1, 1887, read, “seems pretty well received by friends on trial today,” which I take to mean that her friends and family were happy to see her again when she appeared in court to be evaluated for potential release.

Big Changes

The old St. Anthony section of Minneapolis transformed around the LaBelles in their first decade in the city. Between 1880 and 1886 three of the most iconic parts of the St. Anthony skyline were constructed.

First, in 1877, the year before my branch of the LaBelle family moved in, the area’s French Catholics had purchased a twenty-year-old Greek Revival church from the First Universalist Society of St. Anthony and renamed it Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church. The church was located a little more than a block west of the Godfrey House on Prince Street and became the LaBelles’ parish church as soon as they arrived. Between 1880 and 1883, the French Catholics significantly reshaped the structure, “adding a transept, apse and front bell tower with three steeples,” according to Wikipedia. It looks much the same today as it did in 1883.

Second, in 1880, a few blocks to the east of the church and directly across the street from the LaBelles who lived at 419 S.E. 2nd Street , construction began on the world’s largest flour mill. Opened in July 1881, the Pillsbury A-Mill remained the world’s largest flour mill for more than 40 years. I try to imagine the awe the LaBelles must have felt as they watched the six-story behemoth rise from the shoreline. I wonder whether they participated in the intricate dance of workers, machinery, and railcars that took place every day as tons of grain were shipped in and thousands of barrels and sacks of flour were shipped out of the mill. I envision conversations they had about how different their lives were in Minneapolis than they had been on that small farm in Gentilly.

Finally, the most eye-catching structure on the St. Anthony riverfront was built right next to the Godfrey House in 1886. In 1885, Minneapolis boosters organized an industrial exposition fair to be held the following year. Minneapolis had just lost out to St. Paul as the permanent home of the Minnesota State Fair, and Minneapolitans wanted to show off the industrial power of their city. A mostly vacant square between the Godfrey House and Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church was chosen as the site of the new Industrial Exposition Building. The building was completed in August 1886, and the initial 40-day fair attracted almost 500,000 visitors. The building later hosted the 1892 Republican National Convention. However, like so many showpiece buildings constructed for big events rather than long-term functionality, the exposition building struggled to find a purpose after the fair exhibitors left in 1893. The Exposition Building was torn down in 1940. (Wikipedia)

At the start of 1887, the St. Anthony skyline was rather impressive. The LaBelles no longer resided in the Godfrey House, but most of them still lived in St. Anthony, within a few blocks of their original landing spot. They continued to attend Our Lady of Lourdes Church.

Life and Death

Rosalie returned from the asylum to the LaBelle household in the fall of 1887. She had missed the wedding of her daughter Olivine in 1883 and son Cyrille in 1886, but she returned in time to see three more of her children tie the knot. Daughter Celina married Edward Wilson ca.1889, son Ferdinand wed Rosalie Roy in 1891, and daughter Ermine married Victor Langlois in 1892.

My great-great-grandfather Ferdinand took a different occupational path from most of his siblings. After his brothers toiled all day as laborers packing bags of flour into railcars at the Pillsbury Mill or as lumbermen guiding river-borne logs into the city’s sawmills, they could stop by the saloons of Adolph Eisler or Solomon Robitshek and find Ferdinand behind the bar. Ferdinand worked as a bartender in Minneapolis for at least a dozen years and perhaps as many as twenty years. It was at one of these establishments (or a nearby restaurant) that he met his future bride.

Rosalie Roy, or Rose King as she sometimes anglicized her name, grew up on a farm in Corcoran Township, twenty miles northwest of Minneapolis. Rose moved to Minneapolis to find work when she reached adulthood. A family story says she met Ferdinand at the restaurant where she worked. Perhaps the story confused which half of the couple worked in food service or maybe they both did. Perhaps they even worked at the same establishment. Unfortunately, Rose never appears in a city directory as an independent young woman, so the family story is all we have to go on.

I like to think Ferdinand and Rose hit it off because they could each tell stories about the challenges of living with mentally ill parents. Family stories passed down the generations tell us that Rose’s mother Desanges (Bolduc) Roy wept every time an animal was killed on the farm. We may sympathize with her desire not to harm animals, but such feelings did not make for a very good 19th-century farm wife. Rose’s father Elzear, we are told, went “religious crazy.” His religious fanaticism got so bad that his wife and children eventually drove him out of the house. He disappears from records after 1880. I think I have identified him in Minneapolis in 1888 and in Copley near Bemidji in 1900, in each case working as a teamster. But I can’t be 100% certain the records are for the same Elzear. In any case, Rose could match Ferdinand for stories about a dysfunctional home life growing up.

Ferdinand and Rose’s wedding took place at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church. Their first five children were baptized there during the 1890s.

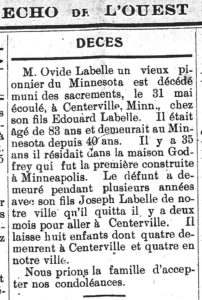

Ovid LaBelle watched his family grow exponentially during the 1880s and 1890s. But along with marriage and birth comes death. At least a dozen LaBelle children in Ovid’s extended family died young during the 1880s and 1890s, including Ferdinand and Rose’s daughter Delima. Ovid’s father Alarie Lebel, patriarch of the family, died in September 1890, age 89. After decades of living with his various children, Alarie’s final year was spent in a Minneapolis “inmate home for the aged.”

More surprising was the death of Ovid’s wife. Almost as suddenly as she had returned, Rosalie (Goudreau) LaBelle died. I was incredibly fortunate to find Rosalie’s death in the parish register of Our Lady of Lourdes (on microfilm at the Minnesota Genealogical Society). The books containing the parish’s burial registers before 1910 are lost. However, a single sheet of paper—two facing pages—survives from one of the older books, containing the last few burials of 1892 and most of 1893. Rosalie’s death was first one recorded in 1893. (Two other LaBelle relatives are listed on the second line of each page: Emma Bazinet, daughter of Calixte Bazinet and Olive Lebel [Ovid’s sister], and Dolphis, son of Joseph Lebel and Anne ??? [Ovid’s nephew Joseph and his wife Eleanora, per cemetery records]).

Riverfront property was valuable property , so Our Lady of Lourdes did not have its own cemetery. Most if not all of the LaBelles who died in Minneapolis were buried in St. Anthony’s Cemetery. The cemetery is located on the 2700 block of Central Avenue, two-and-a-half miles north of the St. Anthony Falls riverfront. It was the primary burial ground for Catholics of many nationalities who lived in the old St. Anthony part of Minneapolis. Remarkably, none of the LaBelles buried at St. Anthony’s Cemetery has a gravestone, They were apparently too poor to afford such luxuries. Perhaps the graves once had wooden crosses, but if they did they have long since disappeared.

Lost History

Two events obscured all of this Minneapolis family history from later generations. First, in late 1899 or early 1900, my great-great grandparents Ferdinand and Rose LaBelle decided to return to their agricultural roots. They left Minneapolis behind to purchase a small farm near Centerville in Anoka County. That farm is where my great-grandfather Alfred LaBelle was raised and where the family linked up with other French-Canadian families that had been in Centerville for several generations. Al had been born in Minneapolis. His baptism is recorded in the parish register of Our Lady of Lourdes. But Al was just an infant when his parents moved to Centerville, and it seems he never knew where he had been born.

Second, in March 1913 Ferdinand’s father Ovid LaBelle moved from Minneapolis into the Centerville home of another of his sons to live out the remainder of his life. He died two months later. Though Ovid had spent most of the previous 35 years in Minneapolis, he died and was buried in Centerville. Ferdinand and Rose are also buried there. To anyone taking just a cursory look back at this family line, it appeared they had always lived in Centerville.

Retracing Their Steps

Two weeks ago, I took my wife, daughter, and parents on a fun day exploring all of this history. Here’s a rundown of what we did, beginning with with two images for reference.

- Tour of the Pillsbury A Mill.

We started the day with a 90-minute guided tour of the Pillsbury A Mill led by staff from the Minnesota Historical Society. Located less than two blocks east of the Godfrey House’s original location, the Pillsbury A Mill was the largest flour mill in the world when it was constructed in 1881. It held the title for decades thereafter. The 1881 city directory lists several LaBelles, including patriarch Alarie, at 419 2nd Street SE, across the street from the magnificent new mill. The mill has recently been remodeled into artist lofts. It was an A+ tour, and it looks like an amazing place to live. - Lunch at Pracna.

Pracna is the oldest bar still in operation in Minneapolis. It opened for business in 1890, which means Ovid, Ferdinand and/or Rose Roy might have dined there. In fact, considering they coexisted for so many years in the same neighborhood, I am confident one or more of my ancestors had a drink at Pracna more than a century ago. In the 1905 photograph snip below, it appears Pracna was build right next to the Godfrey House. However, Pracna sits on Main Street, while the Godfrey House is half a block back on Prince Street. Ferdinand never worked at Pracna, but since he spent about 20 years as a Minneapolis bartender, I had a drink in his honor. (I ordered a Hamm’s, the most historic local brew on the menu. It was first brewed in St. Paul in 1865.)

- Tour of the Ard Godfrey House.

Ard Godfrey House, June 2017. Photograph by author. The Godfrey House is still standing after 168 years, though it has been moved three times in order to preserve it. It now sits in Chute Square, about a block from its original location. The Woman’s Club of Minneapolis owns the house today, and it is open for guided tours on summer weekend afternoons. As I described above, through sheer genealogical fortune, I believe I identified all of the boarders in the Godfrey House in 1880. Though I wasn’t looking for answers about the Godfrey House, since the records about my own family paint a fairly clear picture that they were there, I knew I could help the Woman’s Club fill in the story of the house. When we visited, I donated copies of the documents that link the LaBelles to the house. I also included a copy of an 1885 Sanborn Insurance map and a few parish records from Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church that help show how both the LaBelles and the house fit into the greater community during the 1880s.

- Attempted visit of Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church.

We tried to visit Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church, but our timing was poor. Saturday afternoon around 2:00 is prime wedding time at a Catholic church, and we chose not to saunter down the aisle in our shorts and t-shirts admiring the architecture in the middle of their ceremony. A plaque outside the church says it is located near the spot where Franco-Belgian Father Louis Hennepin became the first European to see the falls of the Mississippi in 1680. Father Hennepin named the falls St. Anthony after his patron saint Saint Anthony of Padua. - Drive past the former Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged.

Now remodeled as an apartment complex, the former Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged was where Ovid LaBelle spent his final years, excepting the last two months when he moved to Centerville. The Home was both yet another legacy of the family’s poverty and a reminder of how much private charities helped out in an era before Social Security. (Location) - St. Anthony’s Cemetery.

To restate what I wrote above, land along the Mississippi River shore was prime real estate, so most churches in old St. Anthony did not have their own cemeteries. LaBelle patriarch Alarie died in 1890 and was buried there. Ovid’s wife Rosalie Goudreau LaBelle died in 1893, and I have to believe she was buried there too. Ferdinand and Rose LaBelle lost an infant daughter named Melina later in 1893. She was also buried there. In fact, more than 15 LaBelles were buried in the cemetery during the 1880s and 1890s. Astonishingly, NONE of them have a headstone or a marked grave of any kind. The families must simply have been too poor to afford them. The only evidence for their presence at St. Anthony’s comes from the cemetery’s register of burials, which ocassionally matches up with surviving parish records from Our Lady of Lourdes.