Mrs. GeneaLOGIC and I are expecting!

You know what that means. It’s time to dive into the family tree to find potential baby names.

How people choose names

Naming a child is a special event. The name we choose will shape other people’s first impressions of him or her from day one and it will affect our child’s self-identity as s/he grows up. It’s a big decision. We took it seriously with our first child, a daughter named Eliza, and we’re taking it seriously again. But how should we choose the best name?

Some people choose names that are popular at the moment. We all know the names that were popular when we went to school. Linda and Bob? 1950s. Jennifer and David? 1970s. I bet you can guess my age pretty accurately if I I tell you is that I was high school friends with triplets named Amanda, Megan, and Sara.

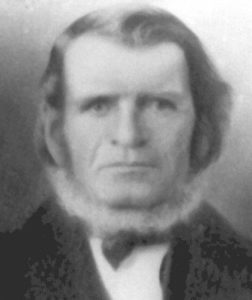

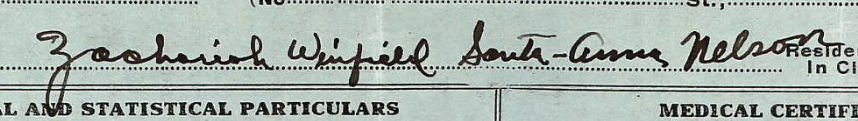

Other people name their children after famous or important contemporary figures. How many of you have a George Washington [Surname] or Thomas Jefferson [Surname] in your family tree? One collateral family in my tree contains sons named John Wesley Nelson, Columbus Washington Nelson, Henry Clay Nelson, George Washington Harrison Nelson, and Zachariah Winfield Santa-Anna Nelson, among others. In the last instance, the parents obviously couldn’t decide which Mexican-American War general they wanted to honor and decided to reference them all.

Many names from European cultures originally carried a literal meaning. Today, people generally don’t know the underlying meaning of most names and only go searching when expecting a baby. But even though people don’t know such meanings by heart, they still affect which names many parents choose for their children.

Biblical names like John or Elizabeth derive from Hebrew and in their original language typically spelled out the child’s relationship to God: Yochanan, “Yahveh is gracious,” or ‘Elisheva’, “My God is abundance.” Most Western versions of Hebrew names passed into common use via a Bible written in Greek or Latin, and so we have inherited Johannes (Latin from Greek) and John rather than Yochanan, and Elisabet (Greek) rather than ‘Elisheva’. For many Christians through the ages, the underlying Hebrew meaning was less important than the name’s association with important Biblical characters.

Other familiar English names originated from archaic forms of Celtic, Germanic, Greek, Italic, or Slavic languages. They likewise originally carried a literal meaning or referred to nature or divinity. Frederick, for example, derives from two Germanic components, frid “peace” and ric, “ruler.” Fiona comes from the Irish word fion, meaning “vine.” Danica was a Slavic personification of the Morning Star, Venus. And so on.

Immigrant groups from outside Europe are adding new names to America’s pool of names and meanings every day. To give just one example, a state congressional district here in Minnesota recently elected former Somali refugee Ilhan Omar as its representative. Fittingly for a politician, her given name means “to state something eloquently” in Arabic. Several names more commonly found in African-American families, such a Imani and Tariq, also derive ultimately from Arabic words and may reflect a much older link to the Muslim communities of East Africa.

For genealogists, family names are especially important. Because our family trees are bigger and we often know them by heart, we typically have more family names to choose from. We can dig deeper into the past to find the best fit. Indeed, one of my stipulations is that the names we choose must come from somewhere in our child’s direct ancestry.

Having said that, choosing a family name is just one of several important factors. There are practical things to consider like spelling in elementary school and job applications as an adult. Here are the general criteria we are using to choose names for for our children, in rough order of importance. (We never formally spelled it out like this. This is essentially a summary of many conversations over dinner and before bed.)

- A name we both like

- Goes well with our last name (probably no alliteration)

- From a direct ancestor (ideally a person who led an interesting or inspiring life)

- Sounds cute for a kid AND respectable for an adult. It has to look good on a resume.

- Standard spelling. Sorry to all the Jaiessuns out there, but why make a simple name more complicated?

- Not in the Top 10 most popular. No offense to the Lindas of the 1950s or the Liams of today, but we don’t want our child to share his or her name with half the school room. A certain degree of individuality is a good thing.

- Not too obscure for the United States in the 21st century. (The flip side of #6.)

- Ancient/original meaning is fitting and aligns with our values

- Initials don’t spell something unfortunate

This genealogist’s first attempt

We named our first daughter Eliza Pauline. It was important to me as a genealogist to find meaning in the names we chose from the personalities or life histories of the namesake ancestors. Ultimately, that’s why we do genealogy, isn’t it? Our ancestors don’t care whether we remember them. They’re dead. But we find meaning in their lives. They help us figure out our place in the world. They may have passed skills or personality traits down to us. They can teach us how to live (or how not to live). Choosing a name of an ancestor for a new child reflects how we, as parents, understand our heritage right now.

The name Eliza comes from my side of the family and Pauline from my wife’s. There are two Elizas in our daughter’s direct ancestry.

Eliza Nelson is my 4x-great-grandmother on my dad’s old-stock American side. She was born around 1810 probably in Frederick County, Maryland. I don’t know many details of her life. In fact, I only have three primary sources that give her name: an 1831 marriage record from Harrison County, Ohio; the 1850 census from Pike County, Illinois; and her gravestone, erected presumably in 1857 when she was buried.

Eliza Kinney was born to Irish immigrants in Canada around 1845. She is my 3x-great-grandmother on my mom’s Irish side. Eliza moved many times in her life. As a girl, she traveled with her parents from Canada to Vermont and then to northern Pennsylvania. In 1864, alongside her new husband James Daly, she moved west to settle with her new family in southern Wisconsin. She left her parents and many siblings behind in Pennsylvania. Only five years later, Eliza was on the move again, this time traveling farther west to cut a new farm out of the prairie in southwestern Minnesota. By age 30, Eliza had already made five major cross-country moves—all without automobiles and mostly without trains. Later in life, Eliza’s family made a final move, another 100+ miles northwest to a farm near the South Dakota border. This Eliza is also a bit of an enigma. After her husband’s death in 1913, I can’t find her again. Her gravestone, marked “1845-1931,” is the only evidence of her whereabouts after 1913.

Though we don’t know much about the personality of either Eliza, we can still draw meaning from their stories. Both Elizas were migrants, especially Eliza Kinney. Like her namesakes, we hope our daughter Eliza goes where life takes her, or rather, takes her life where she want it to go, wherever that may be. Like her ancestors, we hope she grows up to change her own circumstances for the better.

Pauline Shoultz was my wife’s grandmother. We know a lot more about her personality. Even though she was an “old” grandma (she was almost 71 when my wife was born) my wife and her sister got to spend a lot of time with Pauline while they were growing up. I also got to know her a little bit before she passed away. She was a spirited if uncompromising woman of fully German descent. My wife remembered her this way. “She wasn’t like other people’s grandmas—polite, sweet. She was a spitfire with her own sense of humor. Grandma Pauline wasn’t a proper lady. She liked sports and hanging with the old guys at the coffee shop. She said a lot of really funny things, intentionally and unintentionally. At the same time, she was an emotional rock, steadfast and determined.” These qualities helped her live to be 98 years old.

When our daughter Eliza Pauline is a little older, we’ll explain to her why we chose the names we did. We’ll teach her about her ancestors. We’ll share our desire for her to grow into an adventurous, independent woman who is also kind, loving, and loyal.

Great family names . . . for someone else’s child

Yes, we like old family names. There aren’t a lot of Elizas or Paulines these days, but both names fit the resurgence of names that were popular around 1900. Of course, not all old family names make good names in 21st century America. My wife’s 2x-great-grandmother was named Svanhilde. It’s a unique old Scandinavian name that was first documented in the 18th century in the same county in western Norway where our Svanhilde lived. (Her grandmother, born in 1775, was also named Svanhilde and may have been the first recorded bearer of the name since the Viking-age sagas.) I have teased my wife about naming our next child Svanhilde so much that she is frankly tired of the humor. (I think she’s taking our naming duty more seriously than I am.)

With Svanhilde at the head of the list, here’s a list of old family names we will not be using for our next child (but that I like to threaten to write on the birth certificate while my wife is still recovering):

Female

- Svanhilde

- Olga

- Josephte

- Ambjør

- Euphroseine

- Orlaug

- Jacquette

Male

- Ladislav

- Asbjørn

- Ole

- Václav

- Mareen

- Désiré

- Burgess

- Vavřinec

- Gunnar

- Livinus

Yes, all of these are given names in our future child’s direct ancestry. Most of them sound distinctively “ethnic” in 21st century America. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For example, searching the Social Security baby names lists for a few other “ethnic” names from our family tree, I discovered that more than 550 American girls were named Ingrid in 2008 and more than 650 boys were named Johan in 2016. Bridget is an evergreen name of Gaelic/Irish origin.

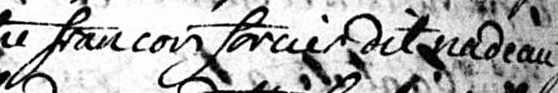

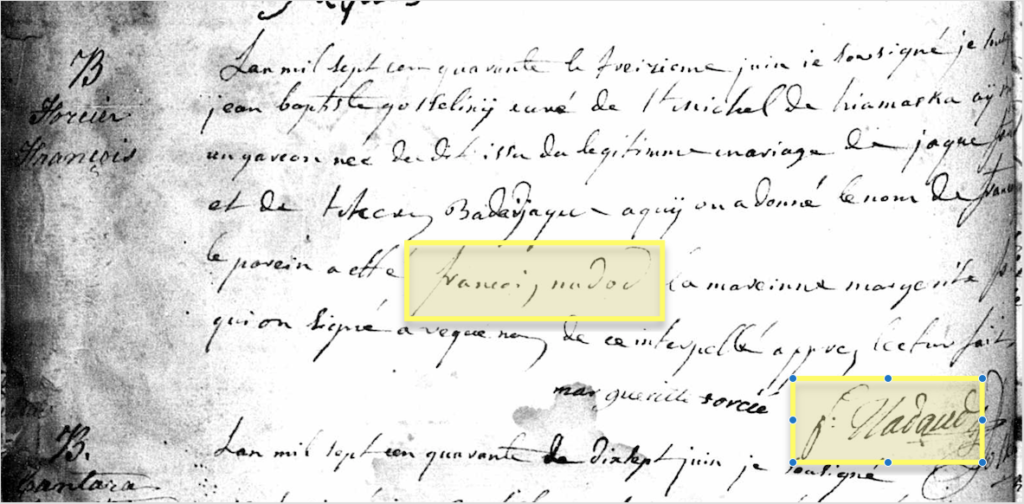

That said, such names do tend to raise questions about where a person is from. Svanhilde, Ambjør, Orlaug, Asbjørn, and Ole are all Norwegian in origin. (They’re “old” names in Norway now, too.) Gunnar is Swedish. Désiré and Livinus are Dutch/Flemish. Ladislav, Václav, Vavřinec, and Olga are names of some of my Czech ancestors. Josephte is a distinctively French-Canadian female name while Euphroseine is a Greek name carried by a handful of my female French-Canadian ancestors. Mareen was a French Huguenot man who settled in colonial Maryland. Burgess is an archaic given name of Scottish or English origin and the given name of Eliza Nelson’s paternal grandfather. All are interesting names for different reasons, but none fit our family in this time and this place.

So which name will we choose for baby #2? Well, you’ll have to wait for a birth announcement! We still have the boy name we chose from my wife’s first pregnancy (and we still like it). We recently agreed upon another girl name. I think we also recently agreed that, just like our first pregnancy, we won’t find out the baby’s sex until s/he is born. We like the mystery. Doing it the old fashioned way also makes naming the child a part of the birth event itself. I still remember calling Eliza by her name for the first time right after she was born. It was moment I’ll never forget.